Eight p.m.

Friday. The Jinn had been in the jar for

exactly three millennia. It sounded simple

when stated in historical terms like this,

and in one sense it was true. If the second

hands on a tiny, hidden clock were to

have been watched constantly for three

thousand years, much as the Museum Curator

was watching his wall-clock at that very

moment, then the seconds would have rolled

into minutes, the minutes into hours and

so on. Neat rolls of time, spiraling up

all the way to heaven.

The Curator shepherded

the last of the cleaners through the already

half-closed side-door, jangling his bunch

of keys like a Victorian station-master.

It was a familiar ritual, as much a part

of the involuntary segments of his life

as, say, brushing his teeth or eating

bread in the morning. The Closing-Up rite

had melded into the thrum of his daily

inhalation and was on the way to becoming

myth (though the Curator knew that this

might well have taken another three thousand

years). By which time, of course, the

small-boned man, along with his obsolescent

side-whiskers might have become part of

the Great Sinai Desert or else a speck

in the eye of the whore on Main Street,

Sacramento, Calif. 1). The next part of

the process would be for him to switch

off all the lights, retire to his tiny

room, and drink old coffee from a stained

mug - the last note in the tapping Arabesque

of his polished floor day. He closed the

side-door, slid the bolts and then turned

three keys in three locks, each one twice.

He re-attached the keys to the large ring

slung from his belt, removed a handkerchief

from his pocket and wiped the top of his

bald pate. He peered at the stain, trying

to focus, but its edges were undefined

and it extended through the white cloth

in all directions at once. He found himself

gazing into some non-existent distance.

Not so much beyond the stain, as between

it. He flipped the hankie over and saw

that his sweat had seeped right through

the material like some kind of insidious

salt cloud. A noise sounded from behind

him. He spun round, then rebuked himself

for reacting. It wasn’t as if he

was unused to the creak and sputter which

the old building generated as night crept

along its wood and glass and stone. There

were so many halls, each arrayed with

dozens of cases, every one of which contained

multiple objects. He reminded himself

that tonight of all nights, it was imperative

that he keep a cool nerve. He held out

both hands, carefully inspecting the finger-tips

for any sign of tremor. He blinked, slowly,

and exhaled. Allowing his arms to swing

in measured pendula, he walked over to

the Temple Case.

The cabinet was the longest

in the museum. Running almost half the

length of the room, it contained relics

thought to have been recovered from the

Temples of Jerusalem, both Old and New.

Many of the contents had only been discovered

on recent archaeological digs, both beneath

the Old City of Rome and in the soil of

a dried-up oxbow lake by the Bosphorus.

They accorded with the set of Temple artifacts

listed in the (possibly apocryphal) Books

of Solomon which themselves had been re-discovered

by one Ben-i-Amin Levi, an octogenarian

Kabbalist while he had been poring over

one particularly faded set of punctuation-marks

in those Nag Hammadi Scrolls which had

been thought to have been burned by the

wife of the peasant who had stumbled across

them in a jar beneath the sands of Egypt

but which, in fact had been sold by her

to a Cairene manufacturer of backgammon

sets. 2

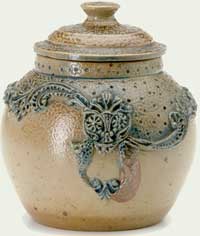

Among the golden brooches

and cryptic candelabras (each as accurately

annotated as possible given the circumstances,

and pinned to the green felt of the cabinet

base) were several large porcelain jars.

All the surahis but one, were unstoppered.

They were of different colours, and each

had a shape and design unique to itself.

Spiral serpents, reclining lions, abstract

geometric patterns, a fish … The

Curator looked at each of the jars, in

turn as he had done every night and every

morning for seven years, ever since they

had been brought to the museum. He couldn’t

bear the thought of any one of them being

stolen. It would be worse than murder.

It would be like pilfering a myth. Stealing

a soul. When he had reassured himself

that all the containers were present and

unharmed, he came at last to the final,

the stoppered jar. It had a sinuous, female

shape and its long, slender neck rose

high above the others. The ancient porcelain

was decorated in blue fire designs. It

was almost totally undamaged. He stood,

motionless beside the cabinet. At first,

he had treated the jar as just one more

relic. He had known, even then, that this

was a lie. A necessary deception. He had

behaved like a fusty academic with a beautiful

woman. He had tried to ignore the surahi,

yet his dreams had been filled with its

dancing, curvaceous form. Sometimes, it

would melt in reverse creation and assume

manifold shapes, multiple existences.

Until at last, he could feel it taking

the shape of the Curator. Becoming, him.

After a few months of this, he’d

had the security sensors around the cabinet

enhanced, so that even the most casual

of glances, the tiniest of envies would

tend to set off the alarm. Then he had

it arranged so that when the bells did

sound, they would cause a red light to

flash, on and off, in his office.

Every morning, he would

arrive before the post was delivered,

and in the evening would exit the building

only after the last of the cleaners had

left. Eventually, even this had not been

enough and he had begun, over the past

few weeks, to sleep behind his office,

in a room hardly bigger than one of the

larger cabinets. He had made excuses to

his wife, saying that an extremely important

consignment had arrived

at the Museum and that someone would be

needed to watch over it at night. ‘Why

you?’ she had asked, ‘Why

do you have to do it? Why don’t

they get someone else for a change?’

and he had replied, ‘Who else would

there be? I have no choice.’ In

some ways he wasn’t lying. And in

spite of the cramped conditions in his

office, he had begun to feel a new kind

of freedom there, one which he could never

have had on the streets or in his home

or in twenty years of marriage. It were

as though time, that most precious of

artefacts, had been suspended in the very

substance of the glass cases, the creaking

wood pillars, the musty, unchanging air.

In the Museum, at night, the Curator felt

he could expand and fill himself. And

yet, the facts remained solid, outside

of him. His marriage, his job, his body…

death. He shivered, though the night was

warm, humid. He felt as though all his

life, he’d been dodging between

pillars of fear, hiding behind first one,

then another till his fear had trapped

him in a temple of pillars. Perhaps that

was why he had become a curator. It was

a safe job. Hermetic, almost. He had slipped

into it as he’d fallen into his

marriage, through a combination of lack

of confidence and his wife’s need

to dominate. He had never quite been able

to handle women. To play them like other

men played the clarinet. He gazed at the

porcelain. It was familiar. Necessary.

He knew every crack, every glaze-line.

He lived along one of those random fissures.

Nothing more. He felt an urge well up

in his chest. An urge to be inside. To

get within. The pressure forced itself

out between his ribs and stretched across

the empty hall. It seemed as though his

life up to that moment had been merely

a preparation for this night.

The

Curator removed a small key from the ring

and unlocked the case. He reached out

and touched the jar. It was fingertip

cool. The temperature within the cabinet

was maintained at a steady level, regardless

of room temperature. But then, he mused,

the room temperature was also kept at

a steady level, winter and summer. His

mind flipped through the convolutions

of a thousand realities, each one hovering

in its own, unique weather-pattern. He

wondered whether, within the jar, there

existed still other, air-conditioned boxes,

right down to an infinitesimal room where

a bald, moustach’d, middle-aged

museum curator was busy wondering whether,

within the jar… 3

The

Curator removed a small key from the ring

and unlocked the case. He reached out

and touched the jar. It was fingertip

cool. The temperature within the cabinet

was maintained at a steady level, regardless

of room temperature. But then, he mused,

the room temperature was also kept at

a steady level, winter and summer. His

mind flipped through the convolutions

of a thousand realities, each one hovering

in its own, unique weather-pattern. He

wondered whether, within the jar, there

existed still other, air-conditioned boxes,

right down to an infinitesimal room where

a bald, moustach’d, middle-aged

museum curator was busy wondering whether,

within the jar… 3

Using both hands, he lifted

the surahi out and placed it on the glass.

Without re-locking the cabinet, he carried

the jar from the gallery down the corridor,

his shoes tap-tapping on the newly-polished

wood of the floor. He cradled it to his

chest. Like a baby, or a heart attack.

Once in his office, he carefully placed

the object on the centre of his desk,

and switched the on kettle. Rituals within

rituals. Safe, he thought, as the water

began to hiss. He sat down. The top of

the jar was at eye-level. The thick bung

which blocked its slender neck was composed

of multiple layers of some greasy material

wrapped, one upon the next, in infinite

jamming roundels. The

blue flames burned along the porcelain.

Kiln-fresh. Repetitive pink motifs circled

the belly of the jar. He saw his face,

his eyes, reflected in the cream white

background. Wondered if something was

looking out at him. He pulled himself

away, went over to a shelf and took out

a large book. Sipping black coffee, the

Curator read from the old tome. Or rather,

he traced his fingers along the esoteric

shapes and numbers within its pages.

The Curator finished reading and reached

out to remove the bung from the top of

the jar. He paused, his hand in mid-air.

The electric light was still on. He got

up and plunged the room into darkness.

Since he had already switched off all

the other lights in the museum, the Curator

found he was totally blind. He stood,

stock-still in the pitch, the only sound

that of his own breathing. Gradually,

that too became merged with the night.

From somewhere, doubts began to slide

up the back of his neck. This whole thing,

and his part in it, was crazy. The jar

had lain in the cabinet for years, and

he had walked past it countless times,

one in the crowd, merely. A spectator.

The lie, again. He had wondered who had

removed the bungs from the other jars,

and what had become of them. And what

had been released from the darkness of

their interiors. It had begun to obsess

him. His

days had become filled with its strange

shadow, its ancient light. His nights

hovered around the jar’s rim, tantalising

him as he craned his neck to get a look

inside. His mind ran on automatic. The

decision had been made gradually, over

the months, and any doubts were now like

the breeze in a candle flame. The Curator

began to make out vague shapes. He stumbled

back to the desk and sat down. His breath

echoed in the jar of his body, and the

harmonics danced along the walls of the

windowless room, chimed within the glass

cases with their spirit objects, blew

cacophonies along the fissures between

the cracked paint and the sinews of the

artist.

The Curator placed his

right hand over the neck of the jar, while

with the left, he pinned the vase to the

table. The bung (he had never touched

it before) felt oily, yielding, beneath

his palm. He wondered what it was made

of. An image of snakes slithered through

his skin. He withdrew. Though they were

not cold, he blew into his hands as though

they were, and tried again. He gripped

the bung, and pulled. It was stuck. His

fingers kept slipping off. Removing a

handkerchief from his pocket, he tugged

and twisted simultaneously, switching

hands after several attempts. As it slid

away from the porcelain, it seemed to

disintegrate and he let it fall. A loud

pop sounded from outside of him. A blinding

light filled his eyes and in the light

he had a momentary vision of the infinite

regression of time and space, before a

whoosh of air gathered up the streets,

the museum, the room, the cabinets, the

jar. He felt the light enter him and fill

him with its clarity. He felt himself

break apart and come together again. All

of his possible existences fragmented

and then evanesced in the light. But in

between fragmentation and re-union, something

had changed. Something in the core of

his being. Then the light faded and died

and the Curator sank into a state which

might have been sleep, but which might

also have been non-existence.

When he opened his eyes,

everything was pink. The jar lay on its

side on the table before him. A long,

grin-shaped crack ran from bottom to top

and blue porcelain flakes had scattered

onto the wood. He reached out and touched

the jar with the tips of his fingers.

It rocked from side to side, and then

became still. Sand on wood. It held no

mystery. He felt his joints move stiffly

as he walked towards the door. A mauve

luminescence streamed in through the high

windows. Dawn was breaking over the museum.

He walked down the hall, passing by the

gray shapes of cabinets, statues, jars,

and in one smooth movement, he threw open

the outer doors. Stepped out. Closed his

eyes. Inhaled. Let the breeze slip over

his face. He opened his eyes and descended

the steps. At the bottom he paused for

a moment and then turned to the right.

Behind him, the doors lay wide open. The

streets were deserted, except for the

odd lone figure trudging back from some

sweatshop night-shift or other. He entered

an early-morning café and sat down.

The only customer. Ordered an espresso

from the blond waiter. Watched him as

he disappeared into the kitchen at the

back. Ran his finger along the wood of

the table. Listened to the sound of the

coffee-machine. Smelled the aroma of morning

cigarettes. Everything seemed so real.

He brought the curator’s coffee

in a demitasse cup balanced on a brass

tray, and again the curator watched him

as he went over to the counter and sat

on a stool. Crossed his legs, took out

a cigarette. He felt the movement of the

waiter’s muscles, the feel of his

hair against the skin of his scalp. He

saw through the waiter’s eyes. Morning

blue. In a harmony of mirrors, he saw

himself. The same, and yet not the same.

The coffee tasted pungent, in the pink

dawn light. The waiter was having difficulty

lighting the cigarette. They were alone

in the café. Just him and the waiter

and the steaming, bubbling coffee machine.

He put down his cup. Met his eye. Looked

away. Then picked it up again but did

not sip. Met his eye, got up, went towards

him. Saw the waiter, seeing him. Blue-on-pink.

Held out his hand, the fingers steady,

porcelain. Flicked the lighter. The waiter

craned his neck and his hair fell across

his olive skin. Just so. He inhaled, twice.

Sat back. Removed the cigarette. Looked

the curator full in the eyes, and smiled.

But already he was smiling back. From

somewhere down the street, the strains

of an old clarinet filtered through the

morning. Single notes. One after the next.

Pure, melismatic. His smile broadened.

The Curator was free.

...............................................................

1 The name afforded to

the western part of the land-mass known

until the late Twenty-First Century as

‘America’. The zone seceded

from the main body of the state after

the Wars Of Intelligence, 2172-2181 and

2186-2190.

2 Codex XVIII, Para 27

(see Bibliography. Solomon, Jar of, Zaragossa

Municipal Library, Sp.).

3 For a discussion of

the dichotomy of the inverted angels of

black magic, see Ahsen, Akhter (1994),

‘Illuminations On The Path Of Solomon’,

Lahore, Pakistan, Dastawez Mutbuat.

.........................................................................................

Suhayl

Saadi

Suhayl

Saadi is a novelist and stage/ radio dramatist

based in Glasgow, Scotland. His hallucinatory

realist novel, 'Psychoraag' (Black and

White Publishing, 2004) won a PEN Oakland

Josephine Miles Literary Award, was short-listed

for the oldest literary prize in the UK,

the James Tait Black Memorial Prize and

a Pakistan National Literary Award and

was nominated for the Dublin-based Impac

Prize and in 2007 will be published in

French by the Paris-based Éditions

Métailié. ‘Psychoraag’

is also used in the curricula of various

universities and secondary schools across

the world. Saadi’s eclectic short

story collection, ‘The Burning Mirror’

(Polygon, 2001) was shortlisted for the

Saltire First Book Prize. His first novel

was a literary erotic fiction, ‘The

Snake’ (Creation Books, 1997), penned

under the pseudonym, Melanie Desmoulins.

He has edited a number of anthologies,

has penned song lyrics for modern classical

compositions, his work has appeared on

several continents as well as widely on

TV, radio, the web and in the national

Press and currently he is writing for

the BBC and the British Council and is

working on another novel. Suhayl Saadi

wishes to acknowledge the valued support

of the Scottish Arts Council. www.suhaylsaadi.com

Suhayl

Saadi is a novelist and stage/ radio dramatist

based in Glasgow, Scotland. His hallucinatory

realist novel, 'Psychoraag' (Black and

White Publishing, 2004) won a PEN Oakland

Josephine Miles Literary Award, was short-listed

for the oldest literary prize in the UK,

the James Tait Black Memorial Prize and

a Pakistan National Literary Award and

was nominated for the Dublin-based Impac

Prize and in 2007 will be published in

French by the Paris-based Éditions

Métailié. ‘Psychoraag’

is also used in the curricula of various

universities and secondary schools across

the world. Saadi’s eclectic short

story collection, ‘The Burning Mirror’

(Polygon, 2001) was shortlisted for the

Saltire First Book Prize. His first novel

was a literary erotic fiction, ‘The

Snake’ (Creation Books, 1997), penned

under the pseudonym, Melanie Desmoulins.

He has edited a number of anthologies,

has penned song lyrics for modern classical

compositions, his work has appeared on

several continents as well as widely on

TV, radio, the web and in the national

Press and currently he is writing for

the BBC and the British Council and is

working on another novel. Suhayl Saadi

wishes to acknowledge the valued support

of the Scottish Arts Council. www.suhaylsaadi.com